best, with a dash of worse attempts at forming a narrative from parts that do not make the same whole, yet it succeeds at doing so when the reader enables its completion. On recognizing the visual language of a family album, readers call into play the personal vocabulary of their own family pictures, and draw upon the archetypal, collective, family album. It is then that the superimposition of two separate yet interrelated sets of conditions, personal and collective, occurs. By making that comparison the viewer accepts, even if not quite realizing it, that there is a mutual cultural language common to family albums that subsequently turns any family album into a part of a collective. The integrity of a personal history, as a set of unique memorable instances, recorded in images that form traditionally family albums, is jeopardized by the awfully similar type of images in this collective family album. The cover of the book is made of a raw book board, into which one Kodak 35 mm color slide is debossed. The slide’s content only becomes apparent upon lifting the cover, and when light can pass through it.

SELECTED PRESS

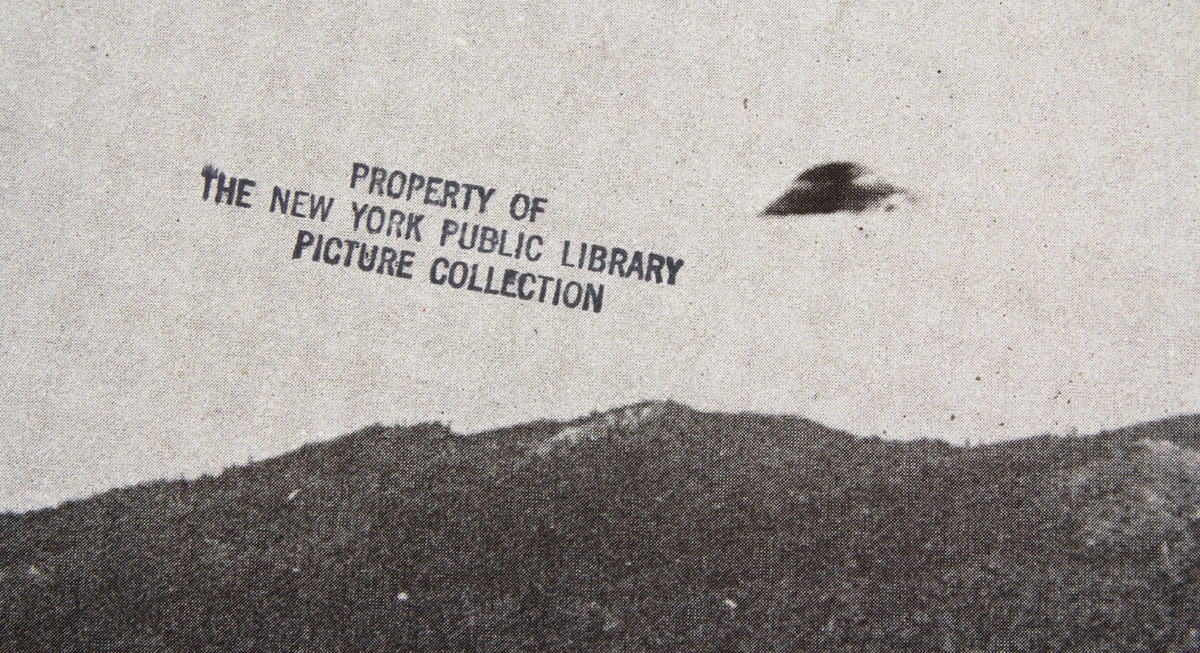

The New York Public Library Picture Collection caches over one million original prints, photos, posters, graphics, magazines, illustrations and texts sorted into thousands of binders, each with a specific category and subject. One binder, “UFOs”, claims to hold and archive our cultural interest in the existence of extraterrestrial life. A binder that was composed into this book. Before Google, the Internet and the ‘age of data’ someone at library attempted to collect and archive the entire volume of visual references published in magazines and newspapers that include pictures and drawings depicting aliens and UFOs. It is needless to say that the alleged attempt failed with a finite number of items in the binder scratching 300 pieces.

In total I checked out 121 items. 121 visual references that represent, according to the binder, our collective memory of UFOs, all of which are directly stamped “PROPERTY OF THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY PICTURE COLLECTION”. It became clear to me that this stamp was more than just an odd archivist’s decision, and now an integral part of the image and its composition. Even more bizarre is the strategic decision of the different archivists who over the years stamped the images themselves, literarily. Not on the back side, above or to its margins, but directly on the art-work, image, drawing or anything of visual importance. In the act and process of “archiving” they ultimately imposed an alien element—altering the context of these cultural gems.

Over the last few years, I have been sending my work to different websites, grants, publications, competitions, exhibitions and more. Alongside some great opportunities and successes, I encountered a lot of rejection. After a period of several months of rejection after rejection, I started to doubt myself and my work. I was on the bus, on my way back home, thinking about all these months that were files with rejections. It started as kind of a joke – about making art out of rejection – and the more I thought about it, the more it made sense to actually do it. While Dear Artist-We Regret To Tell You contains “only” 13 letters, I sent submissions to over 300 places in the last few years. These rejection letters are all the same; none of them is unique, special or more important than the others. The fan format allows you to look at them in no real order; you see them all at once. This book was not made out of anger towards the rejecting places, but more from a place of self-doubt and trying to reclaim my passion as an artist. After I made it, I sent it to all the places I used in my book – wanting to share this with them, to inform them and just to see their reactions.

Edition of 150 | The book is available for purchase - please send email to get information

SELECTED PRESS

The statement that represents the book is the definition of its title – cache memory. The decision to name the book and present it through this definition is handed down as recognition of what is hidden in photographs, coded and read through context; that photographs can unfold memories but not necessarily the same ones that were originally embedded in them. I’m researching a history that I don’t see as actually mine; Family memories that I am not part of. The images become objects that I use in order to create a new history and memory of my own; people and places as I would like to remember and understand them. I started not only looking for my identity in the old photos but also reflect my feelings from these photos on to the world around me. I look for Moments and objects were there is a tension that is created by their incomplete aesthetic. Photography allows me to look at the little and unimportant objects around me and make them a part of my history just by giving them attention. By looking at them I capture them to remember, not letting them go away, yet not trying to save them. Watching their last seconds before I leave and the moment becomes irrelevant, capturing their last breath. With my camera I grant them with eternity and in that I grant myself a memory.

SELECTED PRESS